-

- 메일앱이 동작하지 않는 경우

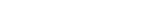

- Window 설정 > 앱 > 기본앱 > 메일에서 메일앱으로 변경

- [해양 > 독도해양법연구센터]2016-12-27 01:16:16/ 조회수 7007

-

미국의 국제합의에 대한 트럼프 행정부의 태도와 법적 함의

- 평가덧글

- 인쇄보내기

- 미국의 국제합의에 대한 트럼프 행정부의 태도와 법적 함의

Kate Birmingham Bontekoe 국제변호사는 최근 미국이 체결한 중요한 3건의 국제합의들, 파리 기후변화협약, 이란과의 핵합의, 환태평양 경제동반자협정에서 탈퇴하겠다고 선언한 트럼프 행정부의 태도와 그에 따른 법적 절차와 영향에 대해 설명하였다.

첫째, 파리 기후변화협약 제25조에 따르면 당사국은 동 협약이 발효한 때로부터 3년 후에 탈퇴 통보를 할 수 있고 그 통보한 때로부터 1년 후에 탈퇴의 법적 효력이 발생한다. 따라서 트럼프 행정부가 탈퇴하더라도 그 탈퇴의 법적 효과는 빨라야 2020년 11월 4일에 발생할 것이고 이때쯤이면 다음 미국 대선이 실시될 것이다.

둘째, 공동포괄계획(Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action)으로 알려진 이란과의 핵합의는 2016년 1월 16일 이행되었으며 이란은 핵무기를 추구, 개발 또는 취득하지 않기로 약속하였고, 유엔 안전보장이사회 상임이사국 5개국과 독일(P5+1) 및 유럽연합은 이란의 핵프로그램에 대해 취해진 제재조치를 해제하기로 합의하였다. 이란 핵합의는 국제법 또는 국내법상 법적 구속력 있는 합의는 아니며, 미국 국무부도 이란 핵합의는 행정협정이나 조약이 아니고 "정치적 약속"에 불과하다고 밝힌 바 있다. 따라서 트럼프 행정부는 언제든지 핵합의를 준수하지 않겠다고 선언하고 이란에 대한 제재를 다시 부과할 수 있다. 다만 미국이 이란 핵합의에서 탈퇴하더라도 나머지 4개 유엔 안보리 상임이사국과 독일, EU는 이란과의 핵합의를 준수함으로써 이란과의 사업관계를 증대시키는 당근과 이란이 핵합의를 불이행할 경우 제재를 다시부과하겠다는 채찍을 동시에 유지할 것으로 전망된다.

셋째, 환태평양 경제동반자협정(TPP)은 역사상 최대 규모의 무역협정이고, 전세계 GDP의 약 40퍼센트와 세계무역의 3분의 1을 차지하고 있는 12개 당사국들(Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, the United States, Vietnam) 간의 관세 인하와 경제관계 심화를 추구하고 있는 조약이다. TPP는7년 간의 협상을 거쳐 2016년 2월 서명되었고, 모든 당사국들이 비준하거나 GDP 합계가 85%에 해당하는 6개 당사국이 비준한 때로부터 2개월 후 발효하게 된다. TPP 제30조 제6항에 따라 트럼프 행정부는 탈퇴를 통보한 때로부터 6개월 후 TPP에서 탈퇴할 수 있다. 트럼프 당선자는 미국의 비준 및 TPP 발효 이전에 탈퇴 통보서를 제출할 것이라고 밝혔다. 예를 들면 빌 클린턴 행정부가 국제형사재판소 규정에 서명한 이후에 조지 부시 행정부가 그 서명을 철회함으로써 조약법에 관한 비엔나협약 제18조상의 조약의 대상과 목적을 저해하지 말아야 할 의무를 회피했던 것과 같은 사례가 될 수 있을 것이다.

* 원문은 아래를 참조.

http://www.ejiltalk.org/what-will-a-trump-administration-mean-for-international-agreements-with-the-united-states/?utm_source=twitter&utm_medium=oupintlaw&utm_campaign=oupintlaw

What Will a Trump Administration Mean for International Agreements with the United States?

Published on December 13, 2016

Author: Kate Birmingham Bontekoe

On 20 January 2017, Donald Trump will become the 45th President of the United States. During the campaign, he spoke often about terminating landmark international agreements concluded by the Obama administration, including the Paris Agreement on climate change, the Iran nuclear deal, the Trans-Pacific Partnership and the normalization of relations with Cuba. Predicting what might actually happen in a Trump administration is difficult, because his statements as a private citizen, candidate and president-elect have been inconsistent. Should he wish to follow through on the campaign rhetoric to take immediate action on these issues, what can the president actually do unilaterally? Decisions to terminate these agreements raise questions under both international and domestic law. The United States is bound under international law when it becomes a party to an international agreement, and also has some limited obligations upon signature. Under US constitutional law, the presidency is at its most independent and powerful in dealing with foreign relations. While that power is not unlimited, soon-to-be President Trump could arguably fulfil all of those campaign promises without violating domestic or international law.

Paris Agreement on Climate Change

On 3 September 2016, the United States ratified the Paris Agreement on climate change which entered into force on 4 November 2016. The agreement was concluded under the auspices of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (“UNFCCC”) which was ratified by the United States in 1992 and entered into force in 1994. The Paris Agreement establishes no binding financial commitments or emissions targets. The states party are bound only to formulate and publish national plans for reducing greenhouse gas emissions to hold the increase in the global average temperature to “well below” 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursue efforts to reduce the increase to 1.5°C. The United States is the second largest emitter of greenhouse gases in the world, and its participation in the Paris Agreement was critical to bringing other states, particularly China, on board.

President-elect Trump has declared man-made climate change a “hoax” perpetrated by China, characterized the Paris Agreement as “bad for US business” and said repeatedly during the campaign that he would pull the United States out of the agreement. In an interview with the New York Times on 22 November, he claimed to have an “open mind” about whether to remain a party. Depending on his views upon taking office, Trump could withdraw from the Paris Agreement, or possibly from the UNFCCC altogether.

Both actions would be legal as a matter of customary international law, under which a state may withdraw from a treaty where the agreement provides an express means for doing so. The Paris Agreement and the UNFCCC both contain such provisions. Pursuant to Article 28 of the Paris Agreement, a party may give notice to withdraw three years after the date the agreement entered into force, and that withdrawal will become effective one year later. Hence, the earliest effective date of a US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement would be 4 November 2020, just in time for the next presidential elections. Withdrawing from the entire UNFCCC would be faster, becoming effective one year after giving notice under Article 25 of the Convention. The US would remain a party to the Paris Agreement prior to the effective date of its withdrawal. Although the agreement does not contain any enforcement provisions should the United States fail to comply with its obligations during that period, several countries have suggested they might impose carbon tariffs on the United States in response.

As a matter of domestic law, because President Obama ratified the Paris Agreement by means of an executive order, which does not require approval of the Senate or Congress, once in office Trump could simply issue a new executive order withdrawing the United States from the agreement. The situation with respect to the UNFCCC is somewhat less clear. The UNFCCC is a treaty pursuant to Article II of the US Constitution, which means it was approved by two thirds of the Senate and then ratified by the president. The Constitution is silent on terminating treaties, and whether a president acting independently is able to withdraw from an Article II treaty is an unsettled question in US law, albeit not a new one. In 1979, President Carter withdrew the United States from the Mutual Defense Treaty with Taiwan. A group of senators sued the President, claiming that withdrawal required consent of two thirds of the Senate. The case, Goldwater v. Carter, reached the Supreme Court which found it non-justiciable as a political question not fit for courts to decide. In 2002, President Bush withdrew from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty (“ABM Treaty”) with Russia. Again, members of Congress brought suit, and the case, Kucinich v. Bush, was also dismissed as a non-justiciable political question. Although no court has ruled on the merits of the issue, treaty termination appears to be considered the prerogative of the president, at least in the absence of specific Congressional legislation in opposition. In this case, the current Republican-majority Congress is unlikely to raise any such objection.

Iran Nuclear Deal

President-elect Trump has also repeatedly threatened to renegotiate or pull the United States out of the Iran nuclear deal, formally known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (“JCPOA”), declaring in March 2016 that his “number-one priority is to dismantle the disastrous deal with Iran.” Under the JCPOA, which was implemented on 16 January 2016, Iran pledged not to “seek, develop or acquire” nuclear weapons and to slow its development of peaceful nuclear energy technology. In exchange, the five permanent members of the UN Security Council, plus Germany (“P5+1”) and the European Union agreed to lift certain UN, EU and national sanctions relating to Iran’s nuclear program. Under the terms of UN Security Council Resolution 2231 endorsing the JCPOA, in the event any of the P5+1 determine Iran to be in significant non-compliance, they could invoke the so-called “snapback” provision to re-impose UN Security Council sanctions.

The JCPOA is not a legally-binding agreement under international or domestic law. Although the UN Security Council endorsed the deal, it did so with horatory language not creating an enforceable obligation on the parties, with the possible exception of the “snapback” mechanism. For the avoidance of doubt, the US State Department went so far as to emphasize that the JCPOA is neither an executive agreement nor a treaty, but rather a “political commitment.” As such, once in office Trump could declare that the United States no longer intends to comply with the deal and re-impose US nuclear-related sanctions that were lifted through waivers and executive actions by President Obama. Renegotiation would be considerably more difficult. As an agreement among seven states and the EU, which took ten years to negotiate, Trump would not be able to insist on better terms without the cooperation of the other parties, none of whom have expressed any interest in doing so.

Despite Trump’s strong criticism of the JCPOA, the risk of alienating the other parties to the agreement, particularly Russia and China, is likely to be sufficient disincentive to tearing up the deal. That said, tensions are already building. On 1 December the US Senate voted to extend the Iran sanctions act for another 10 years. This is largely symbolic as most of the sanctions concerned have been waived in accordance with the JCPOA and will remain so unless Trump backs out of the deal once in office. The Obama Administration stated that this action does not change or breach the JCOPA, but Iran has called the extension a violation of the deal and said it would react, without specifying what it intended to do. It is worth noting, however, that even US withdrawal would not necessarily dismantle the JCPOA. The other parties have stated that they remain committed to the deal with Iran, whatever the United States decides to do. They could potentially keep Iran compliant with the carrot of ever-increasing business ties and the stick of threating to re-impose their own sanctions in the event Iran does not uphold its obligations.

Trans-Pacific Partnership

Throughout the campaign, President-elect Trump excoriated the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade deal (“TPP”) calling it a “continuing rape on our country.” On 21 November, Trump stated that he would exit the agreement on his first day in office.

The TPP is the largest trade agreement in history. It seeks to reduce tariffs and deepen economic ties among its twelve signatories who together represent approximately forty percent of the world GDP and a third of global trade: Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, the United States and Vietnam. The deal was signed in February 2016 after seven years of negotiations and would come into effect either two months after all parties ratify or upon the ratifications by six signatories representing 85% of their collective GDP. Should the United States choose not to ratify, the TPP cannot enter into force under either provision.

Under international law, a state party to the TPP would be able to withdraw under its Article 30(6), and that withdrawal would become effective six months after notice to the depository. Trump, however, intends to “issue a notification of intent to withdraw” before ratification and before the TPP has entered into force, akin to President George W. Bush’s “unsigning” of the Rome Statute of the ICC in May 2002. The possibility of giving such notice, after signature, of an intent not to become a party to the treaty, not to ratify, is contemplated in Article 18 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties and would remove the obligation to refrain from acting contrary to the object and purpose of the treaty.

With respect to US law, the TPP is a congressional-executive agreement requiring congressional approval for ratification, which it does not yet have. Congressional leaders have said they will not take up the agreement during the so-called “lame-duck” session before Trump is inaugurated, leaving the president-elect free to withdraw from the deal.

Cuba

On 28 November, three days after the death of Fidel Castro, referring to the normalization of relations with Cuba, Trump tweeted “If Cuba is unwilling to make a better deal … I will terminate the deal.” It is unclear what Trump would consider a better deal, but it is clear that he could reverse the work of the Obama administration regarding Cuba.

The US commercial, financial and economic embargo of Cuba was established and is enforced by several statutes. Accordingly, only Congress can actually lift the embargo, but the operative legislation was deliberately drafted to give the president wide discretion in enforcement. Within the limits of his discretion, President Obama has taken significant steps to open up the United States-Cuba relationship. For instance, he has restored diplomatic relations, reopened the US embassy in Havana and had Cuba taken off the State Department list of state sponsors of terror. He also eased travel and trade restrictions, permitted US banks greater access and made it easier for Americans to remit money to relatives in Cuba.

As president, although total reversal might be challenging in practice, in theory Trump would be able to undo these changes unilaterally, because they were achieved by executive actions, including executive orders, regulatory changes and presidential policy directives. International law is also no barrier to such action. Although the UN General Assembly has passed resolutions condemning the embargo for 25 years, with only the United States and Israel in opposition – or as of this October, abstention – such resolutions are not enforceable against UN member states.

. . .

In the absence of specific, consistent policy proposals, it is difficult to anticipate what steps Trump will take. To date, members of his transition team and nominees for cabinet posts include climate change skeptics, hawks on Iran and Cuba and opponents of free trade. On the other hand, Trump may be swayed by the considerable business support for these international agreements. The TPP, predictably, is widely supported by US business interests. More than 300 American corporations, including Starbucks, Nike, Levi Strauss, Du Pont and Hewlett Packard, signed a joint letter urging Trump not to withdraw from the Paris Agreement. American travel and tourism companies, including JetBlue, American Airlines, Carnival Cruise Lines and Starwood hotels, have all invested in Cuba since President Obama eased the embargo restrictions. US and international companies, including Boeing, have also slowly begun to reengage in the substantial Iranian market since implementation of the JCPOA. Ultimately, upon entering office, the President-elect will have to balance diplomatic and domestic interests that were not a focus of his campaign, and following through on pledges to withdraw from international agreements may prove more difficult in practice than in theory.